Chapter 00 · Why Learn Linux?

Chapter Overview

Hello, World! In this book's opening, Instructor Liu Chuan shares over a decade of insights gained from learning and teaching Linux systems. Learn Linux the Right Way (3rd Edition) not only builds upon the strengths of its predecessors but also introduces new content and perspectives, aiming to help readers master Linux systems more effortlessly.

Linux's thriving ecosystem stems from its robust open-source community foundation. We'll explore the advantages of learning open-source software and delve into major licenses like GPL, LGPL, BSD, Apache, MIT, and Mozilla—empowering you to make informed choices.

Open-source software offers four key advantages: low risk, low cost, high quality, and high transparency. The open-source spirit is also a source of deep pride for every Linux technologist. Instructor Liu Chuan will narrate the evolution of UNIX and Linux systems since 1969 in an accessible style, peppered with humorous anecdotes.Not only will we trace the evolution of open-source technology over half a century, but we'll also delve into today's top 10 open-source operating systems—RHEL, CentOS Stream, Fedora, Debian, Ubuntu, and more. As we progress, we'll gain a comprehensive understanding of open-source software monetization models and insights into the future trends of the open-source industry.

0.1 About the Author

Author Liu Chuan works in the field of Linux operations and maintenance. Driven by curiosity during high school, he began exploring Linux systems and learning operations techniques at an early age. He earned his RHCE 6 certification in 2012, followed by RHCE 7 and RHCA certifications in early 2015.His 2017 publication, Learn Linux the Right Way, has sold over 100,000 copies and earned him the title of "Outstanding Author of the Year" from POSTS & TELECOM PRESS.In 2020, he attained RHCE 8 certification. The second edition of Learn Linux the Right Way was released in 2021. In 2023, Self-Study Manual for Linux Commands debuted and was honored as "Best-Selling New Book of the Year" by POSTS & TELECOM PRESS, while the author received the "Influential Author of the Year" award.In 2024 and 2026, he successively obtained RHCE 9 and RHCE 10 certifications, solidifying his technical foundation for writing the new edition of Learn Linux the Right Way.

Despite this, I remain acutely aware of my limited capabilities and average technical skills. Without the selfless assistance of numerous mentors and friends, achieving these milestones would have been impossible, let alone completing this book on schedule.Moreover, as an ordinary technologist, I have personally endured the hardships of midnight training sessions, the frustration of six-hour traffic jams, and the tedium of plowing through a dozen dry Linux textbooks. These experiences only strengthened my resolve to write this book.Now, with a heart full of trepidation, I am doing my utmost to continue sharing useful knowledge with readers. I hope this new book can still help everyone avoid some detours and make getting started with the Linux system easier.

I firmly believe that a truly skilled mentor should not merely be a conveyor of technical knowledge, but a distiller of quality insights. Therefore, throughout this writing process, I have consciously avoided cramming every piece of information I know into this book just to show off. Instead, I've proactively discarded impractical content and repeatedly refined the core concepts and challenging aspects from a perspective that genuinely aligns with how beginners learn.The benefits are clear: readers deepen their theoretical understanding while effortlessly mastering practical skills for production environments.

The book you hold is built upon the latest Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) 10 system, yet its content remains universally applicable to most Linux distributions, ensuring broad relevance. All accompanying software and resources are completely free and accessible via www.linuxzone.net.This book guides you from zero to mastering Linux systems, progressively increasing complexity to meet production environment demands for operations personnel. Each chapter includes numerous diagrams, tables, command examples, and review questions. Readers can complete all experiments alongside the text to enhance engagement and reinforce learning.

Finally, I must confess my motivation for writing this book isn't particularly lofty—it's more about settling a debt. For over a decade, countless training institutions in China have profited handsomely, yet not a single one has provided students with a truly excellent textbook. This is a service our learners have long deserved, and we can no longer afford selective blindness.By 2025, my writing motivation has also incorporated a bit of personal ambition—beyond running this book's online learning platform to serve more students and readers, I aim to elevate this free open-source book far beyond the level of paid textbooks from other training institutions. I'm committed to upholding the moral standards of China's open-source community: no deception, no malice, maintaining the purest environment for technical exchange. I invite all readers to hold me accountable.What we seek in return is simple—if you appreciate Instructor Liu Chuan's dedication and find the accompanying services valuable, please share this book with friends and acquaintances, helping more people discover the remarkable work we're doing.

0.2 Learning Is Hard Work

I often wonder if human DNA hides something akin to a Linux environment variable. Let's tentatively call it STUDY_LEVEL! This variable governs our behavior: when set to 1, we become utterly absorbed in learning; when set to 0, we fully embrace life. For most people, this value likely fluctuates around 0.5.Facing the daily choice between study and leisure, we feel like we're stuck in a while(true) loop. I wish some biologist would discover this variable soon—adjusting it higher Monday through Friday, then resetting it to normal on weekends. Just imagining it feels so high-tech. I can't wait for that day to come.

So what should we do until then?

There's only one answer: self-discipline.

Before diving into the study material, I won't sugarcoat this reality—learning is never easy. If someone claims mastering Linux is simple, they're either lying or delusional. At best, it won't land you a high-paying job. Every morning, your mind battles for minutes: should I chat with friends, scroll through TikTok, or open that dreaded "Learn Linux the Right Way" textbook?At such moments, never forget your original dream. Ten years from now, you will thank yourself for the relentless effort you put in today. As the author, my mission is to ensure this book justifies every minute, ounce of energy, and dollar you invest in it—making each completed chapter a tangible step forward.

Writing a book is an arduous endeavor. From the moment I begin drafting to the day it reaches your hands, it often takes two or three years—sometimes even longer. A passage from Mr. Kazuo Inamori’s The Way to Live has always inspired me and served as my foundational pillar of strength. Now, I pass it on to you, the reader of this book:

"Those who approach work half-heartedly, seeking only pleasure in hobbies and games, may gain momentary satisfaction at best. They will never taste the joy and delight that wells up from the depths of their being. Yet the joy derived from work is not like candy—sweet the moment it touches your tongue. It must be distilled from toil and hardship.Thus, the sense of accomplishment when we focus intently, persevere tirelessly, and overcome hardship to reach our goals is unmatched by any other joy in the world. Moreover, since work occupies such a significant portion of human life, if we cannot find fulfillment in labor and work, then even if we find happiness elsewhere, we will ultimately feel emptiness and regret."

This passage made the author realize that true happiness doesn't stem from fleeting entertainment, but from the sense of accomplishment after hard work. Learning skills is no different—every ounce of effort you put in will eventually pay off in the future.

I encourage everyone to grab a pen and jot down your current learning motivation in the space below—whether it stems from interest, work requirements, or the desire for higher earnings, write it down. Since thoroughly reading this book and completing its experiments will take at least 2–3 months, glancing at your note when you feel weary will provide a steady stream of motivation. So, reach across time and space to speak to yourself:

Message to Myself:

Year Month Day

0.3 Open Source Sharing Spirit

Typically, software source code is proprietary. However, open source software (OSS) adopts a more liberal distribution model. Simply put, OSS provides users with both the executable program and its source code. This allows users not only to utilize the software's functionality without restrictions but also to modify the code as needed to better suit their hardware environment and meet specific work requirements. Furthermore, users fully enjoy the freedoms to use, copy, modify, and create derivative works. Under certain licenses, they even possess the freedom to monetize their work commercially.

Yes, you read that correctly—users possess the freedom to create derivative works and monetize them commercially. This means we can deeply customize an open-source software, enhancing its value. As long as the modified software is more user-friendly or introduces novel features while adhering to the original author's license agreement, it is entirely legal to trademark the software and release it as a commercial version. If new users are willing to pay for your software, that becomes your income.This spirit of freedom is precisely what hackers and geeks pursue. Through such collaboration and competition, open-source communities worldwide have gradually developed robust foundations and amassed substantial popularity.

However, if open-source software development solely pursues "freedom" at the expense of developers' interests, it inevitably stifles creative motivation. To balance these interests, over 100 open-source licenses recognized by the Open Source Initiative (OSI) now exist globally to protect the rights of open-source contributors.Those who persistently plagiarize, tamper with, crack, or pirate others' work will eventually face legal consequences.

Considering that you might one day develop a best-selling software as an open-source contributor, this book has curated the top six most popular open-source licenses among developers based on OSI recommendations and practical usage. It also guides you on how to choose among them. Understanding and selecting an open-source license that maximizes protection for your software rights in the future is especially crucial for startups.

Tips:

The terms "open-source license" and "open-source license agreement" are entirely interchangeable; they refer to the same concept and are used here without distinction.

Tips:

The Free Software Foundation (FSF) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to defending the rights of open-source software authors. Its mission is to promote freedom for computer users and ensure unrestricted access to technology. Linux, a quintessential open-source project, was designed and developed based on this spirit of freedom and openness.

Within the open-source community, we frequently encounter the term "Copyleft," a crucial concept developed by the free software movement, often translated as "copyleft" or "public copyright." In stark contrast to traditional copyright (Copyright), Copyleft aims to guarantee software freedom by granting users the right to copy, modify, and redistribute software, while requiring derivative works to adhere to the same free license.

Furthermore, you'll often hear people say open-source software is "free." That's correct—open-source software is indeed free. Here, "free" should never be translated as "free of charge." It actually refers to "freedom"—the freedom to use, study, share, and improve the software without restriction.As Richard Stallman, founder of the Free Software Foundation, famously stated: "Free as in Freedom, not Free as in Beer." This is worlds apart from the meaning of "First drink free" you might see advertised at a bar.

Next, let's explore the six most popular open-source licenses among developers and the rights they grant users.

GNU General Public License (GPL): One of the most widely used open-source software licenses today, granting users the freedom to run, study, share, and modify the software.Originally drafted by Richard Stallman, founder of the Free Software Foundation, the GPL has evolved to its third version. Its core objectives are to ensure open-source community achievements benefit the global community, protect developed software from privatization, and prevent exploitation by unethical software companies.

Under GPL terms, any software incorporating GPL-licensed products or code must remain open-source and freely usable. Consequently, this license is generally unsuitable for proprietary closed-source software products. An enormous volume of open-source software adheres to this license, including the Linux kernel and most other major open-source projects released under GPL. The Free Software Foundation summarizes free software as granting users the four essential freedoms, and the GPL is one of the most important licenses that ensures these freedoms in practice, these freedoms can be understood through the following five practical rights for users and developers:

Freedom to use: Users are free to use the software as needed.

Freedom to copy: Users may copy the software to any computer without restriction on the number of copies.

Freedom to modify: Developers may add or remove features, but modified software must remain GPL-licensed.

Freedom to create derivative works: Users may deeply customize the software and release derivative works under their own name.

Freedom to Charge: Users may sell the software through various channels, but must disclose upfront that the software is freely available. Consequently, open-source software typically generates revenue through paid services like support or customization.

Tips:

Readers may wonder, "Do these open-source licenses hold legal weight? Can they serve as legal grounds?"

In 2008, the Free Software Foundation (FSF) sued Cisco's Linksys division, alleging its routers used GNU software without providing source code as required by the GPL license—a serious violation of the open-source community's rights.In 2009, the parties reached a settlement: Cisco paid damages to the FSF, publicly released the infringing source code, and committed to strengthening internal review mechanisms and purchasing free software compliance training services to ensure strict adherence to the GPL in the future. This case effectively upheld the authority of open-source licenses and set an important benchmark for industry compliance.

Lesser General Public License (LGPL): The LGPL is an open-source license introduced by the GNU Project and supported by the FSF, primarily designed to protect the open-source rights of libraries.Compared to the traditional General Public License (GPL), the LGPL permits commercial software to dynamically link with open-source code without requiring the entire product to be open-sourced. This offers greater flexibility, making it widely adopted by commercial software for referencing library code.Simply put, when using open-source code licensed under LGPL, any code involving that portion—including modified or derivative works—must be released under the LGPL license. Other code outside this scope is not subject to this requirement.

If you feel the LGPL license focuses more on protecting library files than the entire software, you're correct.Originally named the Library GPL (meaning "GPL Library Open Source License"), it's particularly suited for developers who want to incorporate open-source code into their commercial products without fully open-sourcing their entire product. Notable projects like the GNU C Standard Library (glibc), the GTK+ graphical toolkit, and the FreeType font engine all utilize the LGPL license.By ensuring the LGPL-covered code itself remains open-source while permitting linked code to stay closed-source, it supports commercial software sales—truly allowing you to "stand tall and earn money with dignity!"

Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) License: The BSD license is a widely used open-source software license particularly suited for commercial use due to its permissive rules.Compared to the General Public License (GPL), the BSD license offers greater flexibility, permitting users to use, modify, and redistribute software under this license. Additionally, users may release and sell the software as a commercial product. However, to preserve the integrity of open-source code and protect the rights of original authors, three conditions must be met when using the BSD license.

Source Code License Retention: If the redistributed product contains original BSD-licensed code, the license information for that portion must be preserved.

Copyright Notice: If the redistributed product contains only binary files without source code, the original code's BSD license must be explicitly stated in the product's documentation or copyright notice file.

Prohibition of Misuse of Reputation: Unauthorized use of the original software's name, the author's name, or the name of their affiliated organization for marketing purposes is prohibited.

The BSD License permits combining open-source software with commercial products under minimal restrictions. This not only facilitates widespread software distribution but also fosters commercial innovation in technology.

Apache License: As the name suggests, this open-source license is published and maintained by the renowned Apache Software Foundation.As one of the world's most influential open-source foundations, Apache is renowned not only for its widely adopted license but also for developing and maintaining the market-leading web server software—the Apache HTTP Server.Currently, the most widely used version is the Apache License 2.0, released in 2004. This version specifically emphasizes providing developers with comprehensive copyright and patent protections while granting users the freedom to modify and redistribute the code.

The Apache License is particularly well-suited for commercial software development. Numerous prominent open-source projects, including Hadoop, Apache Kafka, and the Apache HTTP Server itself, have been developed and released under this license framework. When developing software under the Apache License, the following three core conditions must be adhered to:

If the program source code is modified, this must be declared in the documentation.

If the software is developed based on another's source code, the original code's license, trademark, patent statements, and other relevant declarations from the original author must be retained.

If the redistributed software contains Apache License code, the original license declaration file must be preserved to ensure users are aware of the software's licensing agreement.

These requirements ensure that software remains open and free while protecting the rights of developers and original authors. This makes the Apache License an ideal choice for advancing open-source software development while accommodating commercial needs.

MIT License: Originating from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and widely recognized, the MIT License was initially applied to the X Window System (X11), hence its early designation as the X11 License. It stands as one of the most flexible and least restrictive open-source licenses, significantly facilitating the free use and widespread dissemination of software.Under the MIT License, users are authorized to use, copy, modify, and redistribute the software. The only requirement is to retain the original software's copyright and license notices in any released software and its derivatives. In other words, the MIT License is remarkably permissive—users can do virtually anything as long as they include the MIT License and copyright information in their code.For instance, the popular JavaScript library jQuery, along with numerous components within the Node.js ecosystem (such as libuv), have adopted the MIT License.

From the design philosophy of this open-source license, I can almost feel the passion and obsession for technology and freedom from those brilliant geeks across the ocean—Mind and Hand (MIT's motto). Let the whole world cheer for open source!

Tips:

Beyond safeguarding your own legitimate rights, you can also adjust the open-source licenses you use to better adapt to the market and expand your user base.

ZeroMQ is a high-performance messaging library widely used in high-throughput and low-latency systems, originally released under the LGPL. In 2013, to attract more developers, its primary maintainers made a pivotal decision—switching to the highly permissive MIT License.This shift significantly lowered participation barriers. Developers could integrate ZeroMQ into various projects more easily without worrying about strict commercial restrictions. Leveraging the MIT License's permissive nature, ZeroMQ rapidly expanded its application scenarios, gained widespread adoption across numerous projects, and achieved significant market share growth.

Mozilla Public License (MPL): Released by Netscape in February 1998 as part of the Mozilla open-source project.At the time, Netscape believed the GPL and BSD licenses struggled to balance developers' need for source code with practical benefits. Thus, by combining the strengths of both agreements, they introduced the MPL. In early 2012, the Mozilla Foundation released MPL 2.0 (the latest version to date), which is widely used in numerous well-known products like Firefox and Thunderbird. The latest MPL license features the following characteristics.

Source code file-level open-source requirement: When utilizing source code licensed under MPL, subsequent use only requires maintaining open-source status for that specific code. Newly developed software features need not be fully governed by this license, and it does not mandate open-sourcing all code in derivatives (somewhat akin to LGPL). This provides greater product and commercial flexibility.

Flexibility for Code Mixing: Developers can combine code licensed under MPL, GPL, BSD, and other licenses within a single project. This flexibility is particularly valuable for complex projects requiring integration of multiple open-source components.

Transparent Change Logging: When releasing new software, developers must include a dedicated file detailing the dates and methods of modifications to the original code. This transparency requirement helps maintain code traceability and fosters sharing and collaboration within the open-source community.

The MPL aims to promote the use and innovation of open-source code while respecting developers' rights and commercial application needs. It bridges open-source and commercial software development, offering an effective way to balance openness and proprietary interests.

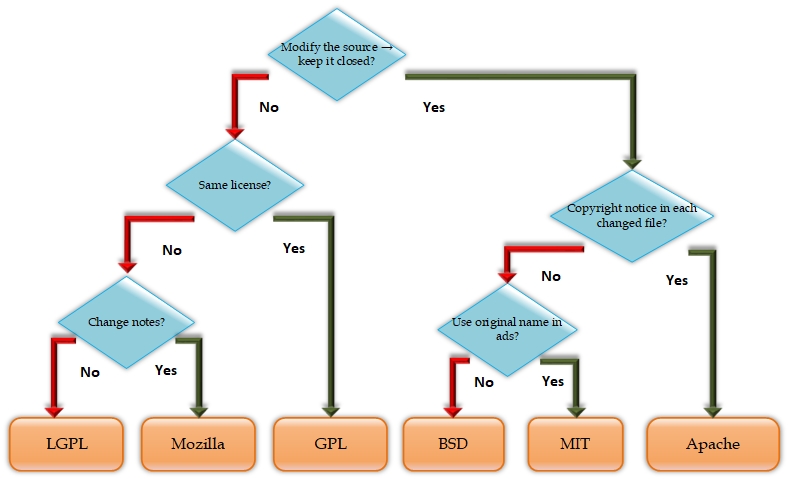

After reviewing this array of licenses, you might find yourself thinking, "Aren't they all pretty much the same? Which one should I choose?" A flowchart created by programmer Paul Bagwell neatly summarizes the six open-source licenses discussed earlier, helping readers make an informed choice. See the diagram below.

As we all know, most open-source software is ready to use right after installation, making it hard to find any pricing information within the software interface. This often leads to questions like: "Instructor Liu, open-source developers need to eat too—how do they make money?" Online, there seem to be only two prevailing views on this:

Passion—Open-source developers are highly motivated and skilled, writing code purely for interest and to benefit society;

Services—First get users to install the software, then profit by offering maintenance services once they're comfortable and reliant on it.

Both explanations hold merit but are incomplete. Readers shouldn't view open-source software as entirely opposed to commercial software, as successful projects also require sound business models. For open-source software, specific revenue models include the following five approaches:

Multiple Product Lines: Cater to diverse user groups by offering tiered products. For example, MySQL databases come in both personal and enterprise editions—the free personal version serves as an excellent promotional tool, while the enterprise edition generates revenue through license sales.

Technical Services: JBoss application server exemplifies this model. While the software itself is freely available, the provider generates revenue through technical documentation, training courses, and custom development services.

Hardware-Software Bundling: IBM typically bundles AIX or Linux systems with server sales to ensure profitability from hardware infrastructure.

Technical Publications: O'Reilly, for instance, operates as both a publishing company and a staunch supporter of open-source software. Many excellent books are published by O'Reilly, and their content often aligns with the open-source projects they champion. A win-win!

Brand and Reputation: Microsoft has repeatedly expressed support for the open-source community. This may surprise some, but it's true! For instance, most of the code for software like Visual Studio Code, PowerShell, and TypeScript is open-source.

0.4 Why Learn Linux?

In class, I often ask students: "Why learn Linux?" Many respond immediately: "Because Linux is open source, so we should learn it." This reasoning is somewhat superficial. There are at least 100 open-source operating systems and tens of thousands of open-source software projects. Why not learn them all? So the open-source nature mentioned earlier is only one advantage—it alone doesn't justify dedicating significant effort to mastering Linux.

For ordinary users, the spirit of open-source sharing merely adds value. What truly matters is Linux's inherent excellence: it offers a UNIX-like elegant and efficient programming interface while inheriting UNIX's rock-solid stability. Moreover, the open-source community continuously contributes high-quality code and extensive third-party software support, enabling Linux to meet the most demanding work requirements in terms of high availability and performance.

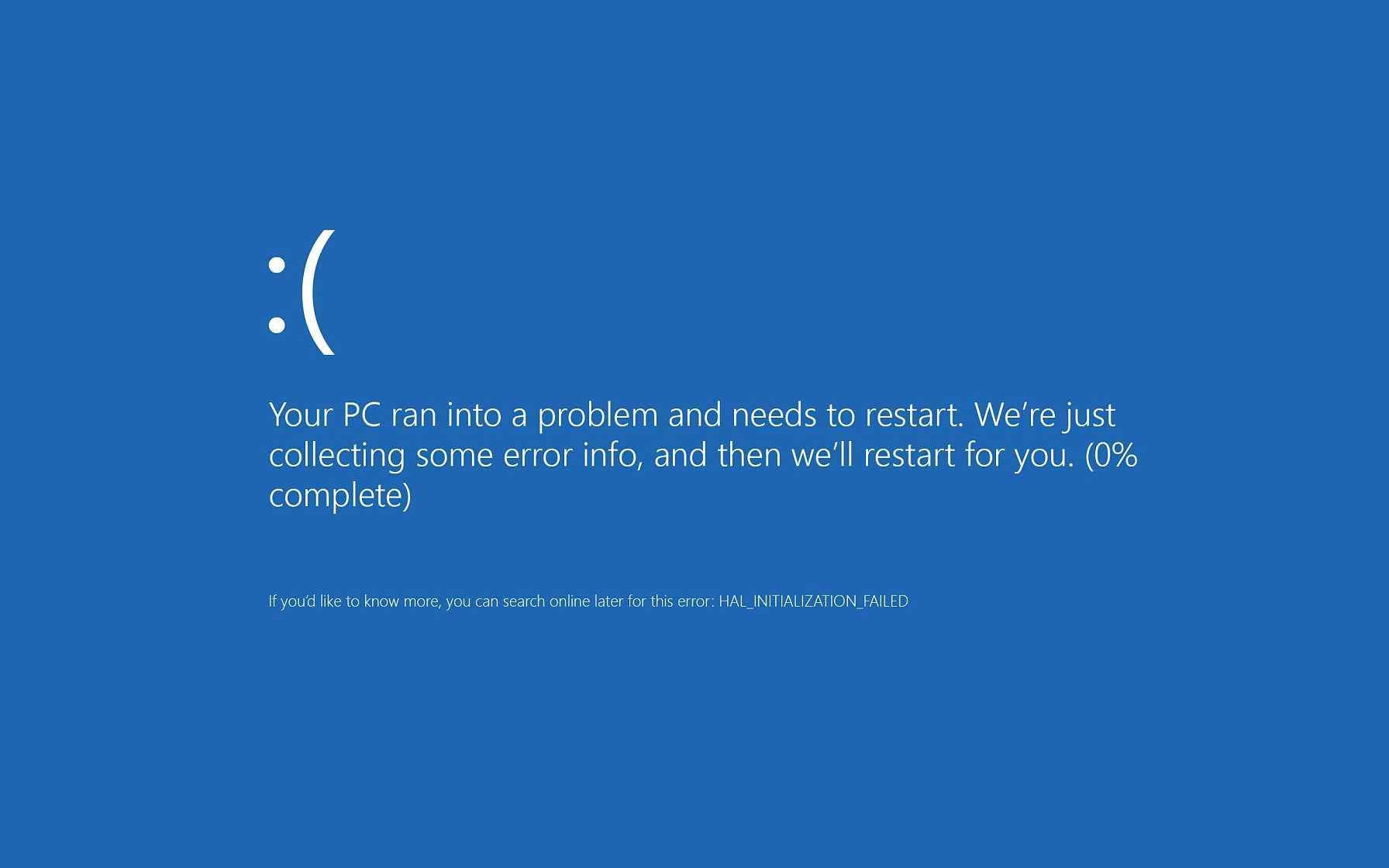

Of course, most readers likely began their computing and networking journey with Microsoft's Windows system, leading to thoughts like: "Windows is perfectly usable and meets everyday work needs." Objectively, Windows is indeed capable, yet it falls short in security, high availability, and performance. You've probably seen this image before. While blue screens aren't commonplace, the consequences of such "incidents" in a production environment are unimaginable.

Therefore, learning Linux isn't just about its open-source nature—it's because it excels in critical performance metrics, providing a solid and reliable foundation for system operation. These characteristics of Linux, combined with the freedom and flexibility offered by open-source, collectively form compelling reasons to learn it.

Linux also holds significant advantages in server and cloud computing domains. Authoritative 2025 data reveals its dominant position in the web server market, accounting for over 90% of high-traffic website servers and becoming the preferred choice for numerous enterprises and developers.

Google's search engine, email services, and cloud platforms all run on Linux. This is unsurprising, as even the widely used Android operating system for mobile devices is built upon the Linux kernel. Furthermore, as the global leader in cloud services, Amazon Web Services (AWS) deploys Linux on over 90% of its servers, underscoring its irreplaceable core position within AWS's public cloud infrastructure.

In the realm of high-performance computing, the TOP500 supercomputer rankings hold significant representativeness. Annually, the world's 500 fastest supercomputers are selected, including the U.S.'s Frontier, Summit, and Sierra; Japan's Fugaku; Finland's LUMI; and China's Sunway TaihuLight.As of this writing, every single one of these supercomputers runs the Linux operating system, underscoring Linux's dominance in extreme performance computing scenarios.

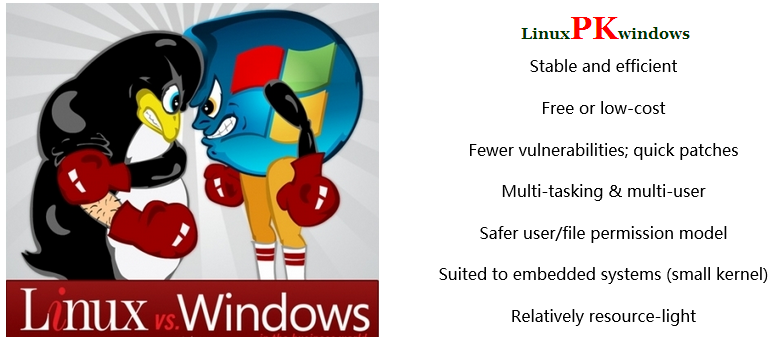

To illustrate the differences between Linux and Windows more clearly, we've summarized and compared them as shown in the figure below. These distinctions are based on Liu Chuan's professional experience. You may not fully agree with them now, but that's okay—you'll gradually appreciate them as you learn.

Frankly speaking, every technologist or developer immersed in the Linux ecosystem feels a genuine sense of pride whenever open-source projects are mentioned—it's a unique sentiment ingrained in their very being.Open-source enterprises aren't solely driven by profit; they thrive on mutual support and strive to serve more customers. Within this ecosystem, the open-source community is inextricably linked with users worldwide. Anyone can contribute their code and ideas, while also benefiting from the collective effort. This virtuous cycle endows open-source software with four key advantages:

Low Risk: Closed-source software creates excessive dependency on a single company, effectively placing our fate in someone else's hands. Should the developers abandon maintenance, we'd be stuck. Moreover, compared to commercial software companies, open-source communities rarely go out of business. Furthermore, once source code is publicly released, even if the original maintainers stop updating it, other developers or organizations can take over, ensuring the project's longevity.

High Quality: Unlike closed-source software, open-source projects are typically developed and maintained by the open-source community. With numerous users contributing to coding, maintenance, and testing, bugs are often fixed before they become widespread issues. Moreover, within an environment of constant idea exchange and iterative code development, developers are unlikely to upload "half-baked" work to the open-source community—after all, their reputation is at stake.

Low Cost: Most open-source contributors work behind the scenes, quietly and voluntarily sharing their work to build a vast ecosystem of open-source software. Leveraging this ecosystem, projects driven by the open-source community can significantly reduce the manpower, resource allocation, and financial investment required for building software from scratch—provided they are properly planned and utilized—thus effectively saving resource costs.

Greater Transparency: No one in their right mind would deliberately embed trojan horses or backdoor code in open-source projects—such actions would inevitably expose their misdeeds to public scrutiny, risking exposure by any vigilant member of the global community.

This unique open-source culture not only delivers high-quality, low-cost software solutions but also democratizes technology, building a robust bridge for technological innovation and global knowledge sharing.

By now, I believe everyone has become familiar with the author's writing style—he never uses a paragraph to explain something that can be conveyed in a single sentence. The benefits of this approach are clear: first, it allows him to pinpoint key points for individual explanation, eliminating verbosity in paragraphs; second, it's complemented by numerous relevant images, making the content engaging and enabling readers to spot the most important knowledge at a glance.Next, I'll summarize the evolution of the Linux system in a few paragraphs, though I won't go into excessive detail. Please pay close attention to each key milestone.

We begin in 1965. To address limitations in server terminal connections and handle complex computations, Bell Labs, General Electric (GE), and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) collaborated to develop a new operating system: MULTICS (Multiplexed Information and Computing System). However, the project's overly complex design led to repeated development setbacks, and it later faced severe funding shortages.In 1969, Bell Labs withdrew from the project, leading to MULTICS's termination. That same year, Ken Thompson—who had worked on MULTICS—wrote a new system kernel in assembly language to run his game Space Travel on the Digital PDP-7 minicomputer. Since this system simplified MULTICS, colleagues jokingly dubbed it UNICS (Unitary Information and Computing System).UNICS gained rapid recognition within Bell Labs for its simplicity and efficiency, becoming the prototype for the later UNIX system.

In 1973, recognizing that the assembly-language kernel of UNICS required rewriting for each different server architecture, creating significant complexity and high barriers to use, Dennis M. Ritchie—the father of the C language—and Ken Thompson decided to rewrite the UNICS system in C.This initiative significantly enhanced the system's cross-platform compatibility, laying the foundation for UNIX's subsequent widespread development and adoption. Through continuous evolution, the UNIX system gradually exhibited characteristics of open-source and sharing, exerting a profound influence on the field of computer operating systems.

In 1979, AT&T, the parent company of Bell Labs, recognized the commercial value and potential of the UNIX system. Despite some opposition within Bell Labs, AT&T resolutely decided to commercialize it.Subsequently, AT&T reclaimed copyrights and progressively restricted the free distribution of UNIX source code, attempting to transform it into a proprietary product for commercial gain. This move disappointed hackers who championed free sharing, dampening the enthusiasm for technical collaboration within the open-source community. However, despite this shift in UNIX's development trajectory, the sharing and advancement of technological achievements persisted in other areas, while the open-source movement continued to seek new breakthroughs and directions.

Faced with such a closed software development environment, the renowned idealist hacker Richard Stallman launched the GNU open-source initiative in 1983 and drafted the famous GPL license in 1989.He aspired to build a more free and open operating system and community. The name "GNU" carries the meaning "GNU's Not Unix!", subtly expressing his stance against commercial UNIX systems.From the project's inception, Stallman took proactive steps, using existing software functionalities as blueprints to lead his team in developing multiple open-source, free utility tools. In 1987, GNU's vision achieved a pivotal breakthrough when Richard and the community collaboratively created a compiler capable of running C language code—the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC).This innovation allowed users to freely compile their C code into executables using the gcc compiler—a revolutionary development that injected a powerful boost into the open-source ecosystem. Like a magnet, it began attracting technologists worldwide, further expanding the open-source community.Subsequently, major products like the Emacs editor and the bash interpreter were released, attracting an increasing number of tech enthusiasts to join the GNU open-source initiative.

In 1984, AT&T still tightly controlled the copyright to the UNIX system, explicitly prohibiting the distribution of its code to students.At this juncture, Dutch university professor Andrew S. Tanenbaum (a forgotten giant in history) developed an operating system called Minix modeled after UNIX to support his teaching. However, it was intended solely for classroom use with no plans for large-scale commercialization. Consequently, Minix gained only modest recognition within academic circles rather than widespread adoption.

Linus Torvalds, a student at the University of Helsinki in Finland, was among those who used it. In August 1991, he developed a new system kernel named Linux using open-source tools like the Bash interpreter and the gcc compiler. He then quietly uploaded version 0.02 of this kernel to a technical forum.This kernel, praised for its high code quality and open-source nature under the GNU GPL license, quickly gained support from the GNU Project and a large community of hacker programmers. Linux then entered a phase of rapid and vigorous development. Linus Torvalds' original post is reproduced below.

Hello everybody out there using minix -

I'm doing a (free) operating system (just a hobby, won't be big and

professional like gnu) for 386(486) AT clones. This has been brewing

since april, and is starting to get ready. I'd like any feedback on

things people like/dislike in minix, as my OS resembles it somewhat

(same physical layout of the file-system (due to practical reasons)

among other things).

I've currently ported bash(1.08) and gcc(1.40), and things seem to work.

This implies that I'll get something practical within a few months, and

I'd like to know what features most people would want. Any suggestions

are welcome, but I won't promise I'll implement them :-)

Linus torvalds

The Linux mascot is named Tux, a cute and clumsy little penguin. Legend has it that Linus Torvalds was bitten by a penguin during a childhood visit to an Australian zoo, so he chose this species as the mascot as a form of "revenge."Whether this story is true remains unverified, but thankfully it was a penguin and not a tiger or lion—otherwise, changing the logo wouldn't have been so simple.

In 1993, Bob Young and Marc Ewing co-founded Red Hat, releasing the first Red Hat Linux version the following year. As a founder, Bob Young significantly advanced Linux adoption through a business model centered on providing technical support and services.After 1998, as the GNU open-source initiative and Linux gained momentum, major IT giants like IBM and Intel joined the movement, significantly accelerating open-source software development. This shift is widely regarded as a pivotal turning point in the open-source landscape.In 2012, Red Hat became the world's first open-source company to achieve annual revenue of $1 billion. It has since surpassed this milestone repeatedly, with annual revenue climbing to $2 billion, $3 billion, and beyond—continuously setting new industry records.

Today, the Linux kernel has evolved to version 6.x, with hundreds of derivative systems. Its development and maintenance embody the collective efforts of developers worldwide. As its founder, Linus Torvalds continues to play a pivotal role in guiding core architecture and making critical decisions. Meanwhile, Red Hat leverages its deep technical expertise and mature business model to hold a pivotal position in the open-source landscape. It stands not only as a leader in commercializing Linux systems and advancing its technology but also as a major driving force behind the evolution of the open-source ecosystem.

0.5 Common Linux System Versions

Before delving into common Linux versions, let's clarify two concepts: the Linux kernel and Linux distributions.

The Linux kernel is the core component of the operating system, initiated by Linus Torvalds and maintained collaboratively by a global developer community. It provides the system's core programs for hardware abstraction, disk and file system control, and multitasking capabilities (detailed in Chapter 2).

A Linux distribution (Linux Distribution) refers to a complete operating system built upon the Linux kernel, bundled with various software components (such as shells, desktop environments, applications, etc.).

Globally, hundreds of distinct Linux distributions exist, each with unique characteristics and target audiences—some emphasize stability and security, others focus on free usage, while others highlight strong customization capabilities, each excelling in different areas. Below, we introduce the top 10 most popular distributions from a user perspective.

Tips:

Throughout this book, "Linux system" will be used interchangeably with "Linux distribution system."

RHEL, Red Hat Enterprise Linux

Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL): As mentioned earlier in the history of Linux development, Red Hat Inc. deserves top billing as a globally renowned open-source technology provider.Founded in 1993 and listed on NASDAQ in 1999, Red Hat has progressively strengthened its industry leadership since 2006 by acquiring dozens of high-tech enterprises and premium technical resources. These include JBoss—a pioneer in open-source middleware—the widely adopted community enterprise operating system CentOS, and Inktank (a core driver of Ceph enterprise-grade storage technology).In 2019, IBM acquired Red Hat for $34 billion, propelling Red Hat onto a path of robust growth in both software and hardware.

Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) debuted in 2000, with Dell, HP, Oracle, and IBM immediately announcing support for the system, offering compatibility certifications and commercial support. Over the following two decades, RHEL's reliable performance and comprehensive services drove a significant upward trend in its market share, establishing it as one of the world's most widely used Linux systems.Numerous Fortune 500 companies, including airlines, telecommunications providers, commercial banks, and healthcare organizations, rely on RHEL to deliver critical services. Renowned for its exceptional stability, Red Hat leverages a global technical services network to provide comprehensive, timely support, ensuring systems operate reliably and efficiently.

The latest version of Red Hat Enterprise Linux is RHEL 10, which is also the default operating system used in this book and Red Hat certification exams. With new support for GCC 14, Rust 1.82, Python 3.12, and LLVM 19, RHEL 10 significantly boosts developer productivity and is sure to impress you.

CentOS Stream Community Enterprise Operating System

Community Enterprise Operating System(CentOS): Originally built by the open-source community in 2004 based on Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) source code, "free" has always been its most widely recognized label.If you ask a seasoned system administrator why they choose CentOS, they won't cite enhanced security or stability—just two words: free! Since Red Hat Enterprise Linux is open-source software, anyone has the right to modify it and create derivatives. CentOS achieves this by removing all paid features from RHEL, recompiling the new system, and releasing it for free public use.CentOS inherits RHEL's stable and reliable system characteristics while allowing users to experience functionality nearly identical to Red Hat Enterprise Linux without paying commercial licensing fees. This has earned it the support of millions of users.

As CentOS is a modified version based on Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) source code, it does not undergo large-scale new feature development like independent distributions. However, the open-source community continues to maintain it through security updates and minor bug fixes.CentOS version numbers typically correspond to RHEL releases—for example, CentOS 8.0 aligns with RHEL 8.0, CentOS 8.1 with RHEL 8.1, and so on.Furthermore, software packages between CentOS and RHEL systems are mutually compatible. This means that if you are working with RHEL but only find a CentOS software repository for a particular application during installation, you can still install that software normally.

In January 2014, the CentOS project was acquired by Red Hat, Inc. and was renamed CentOS Stream in 2019.CentOS Stream inherits its predecessor's free nature, but fundamentally, it is no longer merely a derivative of RHEL. Instead, it functions as a rolling preview of RHEL, allowing users and developers to experience features from the next RHEL release without conflicting with RHEL's commercial model.

Fedora Linux

Fedora Linux: The Chinese translation of "Fedora" literally means "light-top soft felt hat," which bears little relation to the Linux system. Consequently, most people simply transliterate it as the "Fedora" system.Fedora Linux is an official product of Red Hat Inc., originally developed to build and test third-party software for Red Hat Enterprise Linux, fostering the earliest open-source communities. Fedora typically releases a new version every six months and currently serves millions of users worldwide.

Fedora primarily targets desktop users, comparable to Microsoft's Windows 11. Its audience consists of those seeking cutting-edge technology rather than long-term stability. Users gain access to the latest software, which is later ported to Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) once matured. Consequently, Fedora is often called the "testing ground" for RHEL.System administrators seeking to continuously expand their Linux knowledge and maintain technical leadership should closely monitor the evolution and new features of such Linux distributions, continually adjusting their learning focus.

ROCKY Linux

Rocky Linux: In 2021, Gregory Kurtzer, one of the original co-founders of the CentOS project, launched Rocky Linux.This system emerged in response to Red Hat's shift in CentOS strategy (discontinuing CentOS Linux maintenance in favor of CentOS Stream). Rocky Linux is also built from RHEL source code, aiming to fill the market gap left by CentOS's discontinuation. It returns to a community-driven operational model and promises users permanent free access.Users can transition seamlessly from RHEL or CentOS to Rocky Linux, with full compatibility in operations and software packages—a critical feature ensuring enterprise users can continue using familiar environments and tools without major changes after migration.

Furthermore, Rocky Linux provides up to 10 years of lifecycle support per release, ensuring enterprises receive security updates and maintenance services over an extended period. This avoids frequent system upgrades or replacements, making it highly attractive to enterprise users prioritizing system stability and security.Rocky Linux is committed to delivering commercial-grade quality in a free open-source system, upholding the open-source ethos for continuous development. It is poised to become a strong successor to CentOS Linux, continuing its legacy of excellence in the open-source operating system landscape.

Debian Linux

Debian Linux: A Linux distribution adhering to the GNU open-source philosophy, with a long history dating back to its initial release in September 1993.The name Debian combines the surnames of its founder, Ian Murdock, and his girlfriend, Debra. Some translations refer to it as the "Butterfly Transformation" system—a romantic and poetic moniker. Unfortunately, domestic users didn't embrace this interpretation. Instead, they fixated on the concentric circles in the logo and stubbornly mispronounced it. Over the years, the "Butterfly Transformation" name has become increasingly obscure.

Debian is renowned for its stability and security, offering free basic support and compatibility with multiple hardware architectures. Its official software repositories house over 50,000 open-source applications, earning it high recognition and adoption internationally. Though also built on the Linux kernel, Debian differs from Red Hat products in practical operation—for instance, RHEL uses YUM and DNF for software installation, while Debian employs the APT tool.

Ubuntu Linux

Ubuntu Linux: Ubuntu is a Linux system modified and derived from Debian, supporting diverse environments including desktops, servers, and cloud computing. It follows a six-month release cycle.The Chinese transliteration "Wubantu" originates from the Bantu languages of Southern Africa, meaning "I exist because of the existence of others." This embodies a value of humility and gratitude, carrying a profoundly positive connotation.

The first version of Ubuntu was released in October 2004. The Ubuntu Foundation was established in July 2005. Subsequently, Ubuntu expanded its development branches to include desktop, server, and mobile operating systems.Ubuntu is estimated to have tens of millions of users worldwide. Although derived from the Debian system, Ubuntu features deep customization, meaning software compatibility between the two isn't always guaranteed. Canonical now provides commercial technical support for Ubuntu. Long-term support (LTS) versions of the desktop edition receive free support for 5 years, while the server edition can extend support up to 10 years.

openSUSE Linux

openSUSE Linux: A Linux distribution originating from Germany, it enjoys significant recognition across Europe. The openSUSE desktop edition is clean, lightweight, and user-friendly, while the server version offers rich functionality and exceptional stability—even accessible to novices.Though openSUSE boasts significant technical strengths and its large green chameleon logo is widely beloved, its journey has been fraught with challenges. SuSE Linux AG, the company sponsoring and developing the system, was acquired by Novell in 2003 due to poor performance. Novell itself faced operational difficulties and was subsequently acquired by Attachmate in 2011.In 2014, Attachmate was acquired by Micro Focus, which operated the openSUSE maintenance team as an internal department. Starting in 2018, the openSUSE community resumed independent operations, forming an open-source project separate from the enterprise edition.

Despite these changes, openSUSE continues to evolve. Users retain complete freedom to choose their software and desktop environments, including GNOME, KDE, Cinnamon, MATE, LXQt, Xfce, and others. Additionally, openSUSE offers tens of thousands of free open-source packages spanning diverse domains from office productivity to development tools.

Kali Linux

Kali Linux: Compared to the cute chameleon above, Kali Linux's logo appears rather fierce, giving off a tough-to-mess-with vibe.This system is typically used by hackers or security professionals as a platform for conducting penetration testing on websites—in layman's terms, it enables "attacking" websites. Kali Linux evolved from BackTrack, designed specifically for digital forensics and penetration testing. It comes pre-loaded with over 600 cybersecurity tools, including renowned utilities like Nmap (network scanning), Wireshark (packet analysis), and SQLmap.

Kali Linux boasts exceptional compatibility, running not only on personal computers and corporate servers but also on palm-sized Raspberry Pi devices. This makes it feel like carrying a portable arsenal—it truly deserves its own dedicated book.

Tips:

The two most common desktop environments in Linux systems are GNOME and KDE. Kali Linux allows users to choose their preferred environment, while other systems typically default to GNOME.

Gentoo Linux

Gentoo Linux: Translated into Chinese as "Papua Penguin."Finally, a name connected to Linux's mascot—the penguin. The Gentoo penguin is a medium-sized species. Though they appear clumsy, they possess remarkable swimming abilities, reaching speeds of up to 36 kilometers per hour—what agile little chubby creatures!

Gentoo's defining feature is its complete freedom for user customization. Developer Daniel once stated: "Gentoo was designed to let users do whatever they want, without restrictions."Once you grasp this principle, further explanation becomes unnecessary. In Gentoo, every component—including core system libraries and compilers—can be recompiled by users. Customization also extends to selecting preferred patches or plugins. However, Gentoo's extreme flexibility comes at the cost of complexity, making it suitable only for experienced system administrators. It is not recommended as a beginner's first Linux distribution.

Deepin Operating System (deepin)

Deepin Operating System (Deepin): Over the past two decades, several domestically developed operating systems based on secondary customizations of open-source systems have emerged, but most failed to thrive. Deepin stands out as one of the few successful cases that effectively combines technological R&D with commercial operations.According to Deepin's official introduction, the system was initially developed by Wuhan Deepin Technology Co., Ltd. based on Ubuntu. Since 2015, it has adopted Debian as its foundation, offering 32 language versions. To date, it has accumulated nearly 100 million downloads, with users spanning over 100 countries and regions.

Deepin's most compelling feature remains its localization efforts. It comes pre-installed with commonly used domestic software like WPS Office, Sogou Input Method, and Youdao Dictionary, making it highly user-friendly for beginners. Of course, we must acknowledge and confront the fact that Deepin's technological R&D capabilities still lag behind international standards.

In summary, while the aforementioned Linux distributions may differ significantly in interface or operational methods, any system developed based on the Linux kernel is classified as a Linux system. This book is written based on the newly released RHEL 10 system, and its content and experiments are fully applicable to current mainstream Linux systems.This means that after completing this book, you will be equally capable of managing production environments deployed with CentOS Stream, Fedora, Rocky Linux, or other distributions. More importantly, the ISO system images included in the supplementary materials align closely with the Red Hat RHCSA and RHCE exams, making this book highly suitable for candidates preparing for Red Hat certifications.

Download link for the accompanying ISO system image: https://www.linuxzone.net/tools

0.6 Thank You for Your Trust and Choice

First, thank you to all readers for choosing this book among the many Linux publications available. Your support and trust mean a lot, and I promise not to let you down.

Second, I extend my gratitude to every team member who fought alongside me. Listed in order of joining: Pang Zengbao, Zhang Hongyu, Zhang Zhenyu, Wang Hao, Guo Jianpeng, Ni Jiaxing, Jiang Xianhe, Feng Ruitao, Yang Binbin, Wang Huachao, Wang Yanmin, and Yue Yong.Thank you for trusting me and for charging forward together toward our shared goals. Without your help and support, none of our current achievements would be possible. Over the past decade, we've grown from a small blog with just a dozen daily visitors into a technical community now receiving nearly 100,000 daily visits. In the last five years alone, we've launched nearly 60 QQ technical discussion groups (QQ is a popular instant messaging platform in China), with total users exceeding 200,000. Our WeChat public account (a content and community channel on China's most widely used messaging app) has grown from zero to 400,000 followers—achievements unmatched by any domestic technical publication. Especially in the last three years, our growth has far outpaced all industry news sites and educational institutions. High-quality content and strong reader reputation have made each step more solid. We can now proudly say: "Our dedication has retained our users, and they recognize our hard work."

Once again, our gratitude goes to Editor Fu Daokun of POSTS & TELECOM PRESS. It was you who first proposed publishing Learn Linux the Right Way in 2015 and helped refine the book's content to its best possible state, ensuring sales smoothly surpassed 100,000 copies. Thank you for your trust and support over the past decade. Together, we have journeyed to bring this book to its third edition.I extend my gratitude to Professor Wang Tingmei of Beijing Union University. During my Master's studies in Education, she provided professional guidance and dedicated mentorship. It was you who guided me into the fields of Education and Computer Science and Technology. I remain forever grateful to my mentor and alma mater.

Finally, my deepest gratitude goes to my parents and my wife. When I first proposed writing a technical book, you believed in me and supported me without reservation. My wife understands the pressures of my work and actively partners with me in managing the operations and student support for our online training programs, freeing up more time for me to focus on writing. Without your trust and companionship, I cannot imagine the path my life would have taken.