Chapter 10 · Deploying Static Websites with Apache

Chapter Overview

In this chapter I first explain what a web service is and what it’s used for, then compare today’s mainstream web servers so you understand their strengths and characteristics. Next, I walk through Apache httpd’s “global directives,” “per‑site (section) directives,” and “comments,” and show you how to configure them correctly in real deployments so you truly master the way services are configured on Linux.

I also cover what SELinux does, its three operating modes, and how to manage its policies, so that you can configure SELinux domains and file security contexts with confidence. After that, I guide you through several practical labs that use Apache httpd: the basic deployment, per‑user home pages, password authentication, and virtual hosts built by IP address, by hostname (domain), and by port.

10.1 Web server software

In 1970, ARPANET—the forerunner of the modern internet—had already taken shape and began opening to non‑military institutions. Although it connected only four hosts back then (smaller than many of today’s LANs), it laid a solid foundation for the progress of networking technology.

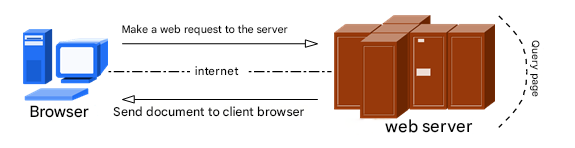

Most of us first touched the internet by visiting a website. A “web service” lets users access resources through a browser. As shown in Figure 10‑1, a web server is a passive service: it only responds after receiving requests from other hosts. The server returns the requested content using HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) or HTTPS (HTTP Secure).

On today’s Linux servers, the most common web service programs are IIS, Nginx, and Apache. IIS (Internet Information Services) is Windows’ default web server. It’s a graphical management tool that can provide not only web sites but also FTP, NNTP, SMTP, and more. IIS, however, runs only on Windows, so it’s out of scope for this book.

Figure 10-1 Communication between a host and a web server

On October 4, 2004, Nginx debuted for a major Russian portal. As a lightweight web server, it quickly gained market share due to its stability and rich features. Its low resource usage and high concurrency are particularly admired, which is why many Chinese portals—Sina, NetEase, Tencent—favor it. I’ll cover Nginx in Chapter 20.

Apache is one of the most widely deployed web servers. It’s cross‑platform and secure, and exposes a fast, reliable, simple API for extensions. Figure 10‑2 shows the famous Apache Software Foundation logo. The name derives from a Native American word that suggests “superior tactics and great patience.” Apache runs on Linux, UNIX, and even Windows. It supports virtual hosts by IP, hostname, and port; multiple authentication methods; proxy modules; SSL/TLS; real‑time status; customizable logs; and a very rich module ecosystem.

Beyond its market share, Apache is the default web server on RHEL 10 and a required topic for the RHCSA and RHCE exams. From both a practical and certification perspective, it’s worth learning to deploy Apache and its features in depth.

Figure 10-2 Apache Software Foundation logo

Overall, Nginx—as a later challenger—has earned a huge number of fans on its merits. Our book’s companion site, https://www.linuxprobe.com, is deployed with Nginx. It’s excellent!

Let’s quickly review how to set up local repositories.

Step 1: Mount the installation ISO at /media/cdrom.

root@linuxprobe:~# mkdir -p /media/cdrom

root@linuxprobe:~# mount /dev/cdrom /media/cdrom

mount: /media/cdrom: WARNING: source write-protected, mounted read-only.

Step 2: Create the repository file (see §4.1.4 for option meanings).

root@linuxprobe:~# vim /etc/yum.repos.d/rhel10.repo

[BaseOS]

name=BaseOS

baseurl=file:///media/cdrom/BaseOS

enabled=1

gpgcheck=0

[AppStream]

name=AppStream

baseurl=file:///media/cdrom/AppStream

enabled=1

gpgcheck=0

Step 3: Install Apache. The package name is httpd. Use -y to skip prompts.

root@linuxprobe:~# dnf install httpd -y

Updating Subscription Management repositories.

Last metadata expiration check: 0:00:05 ago on Sun 23 Mar 2025 01:24:37 AM CST.

Dependencies resolved.

================================================================================

Package Arch Version Repository Size

================================================================================

Installing:

httpd x86_64 2.4.62-4.el10 AppStream 54 k

Installing dependencies:

apr x86_64 1.7.3-10.el10 AppStream 132 k

apr-util x86_64 1.6.3-20.el10 AppStream 101 k

apr-util-lmdb x86_64 1.6.3-20.el10 AppStream 17 k

httpd-core x86_64 2.4.62-4.el10 AppStream 1.5 M

httpd-filesystem noarch 2.4.62-4.el10 AppStream 17 k

httpd-tools x86_64 2.4.62-4.el10 AppStream 88 k

redhat-logos-httpd noarch 100.0-2.el10 AppStream 18 k

Installing weak dependencies:

apr-util-openssl x86_64 1.6.3-20.el10 AppStream 18 k

mod_http2 x86_64 2.0.29-1.el10 AppStream 169 k

mod_lua x86_64 2.4.62-4.el10 AppStream 61 k

Installed:

apr-1.7.3-10.el10.x86_64 apr-util-1.6.3-20.el10.x86_64

apr-util-lmdb-1.6.3-20.el10.x86_64 apr-util-openssl-1.6.3-20.el10.x86_64

httpd-2.4.62-4.el10.x86_64 httpd-core-2.4.62-4.el10.x86_64

httpd-filesystem-2.4.62-4.el10.noarch httpd-tools-2.4.62-4.el10.x86_64

mod_http2-2.0.29-1.el10.x86_64 mod_lua-2.4.62-4.el10.x86_64

redhat-logos-httpd-100.0-2.el10.noarch

Complete!

Step 4: Start httpd and enable it at boot so it continues to serve content.

root@linuxprobe:~# systemctl start httpd

root@linuxprobe:~# systemctl enable httpd

Created symlink '/etc/systemd/system/multi-user.target.wants/httpd.service' → '/usr/lib/systemd/system/httpd.service'.

Step 5: Open HTTP in the firewall.

root@linuxprobe:~# firewall-cmd --permanent --add-service=http

success

root@linuxprobe:~# firewall-cmd --reload

success

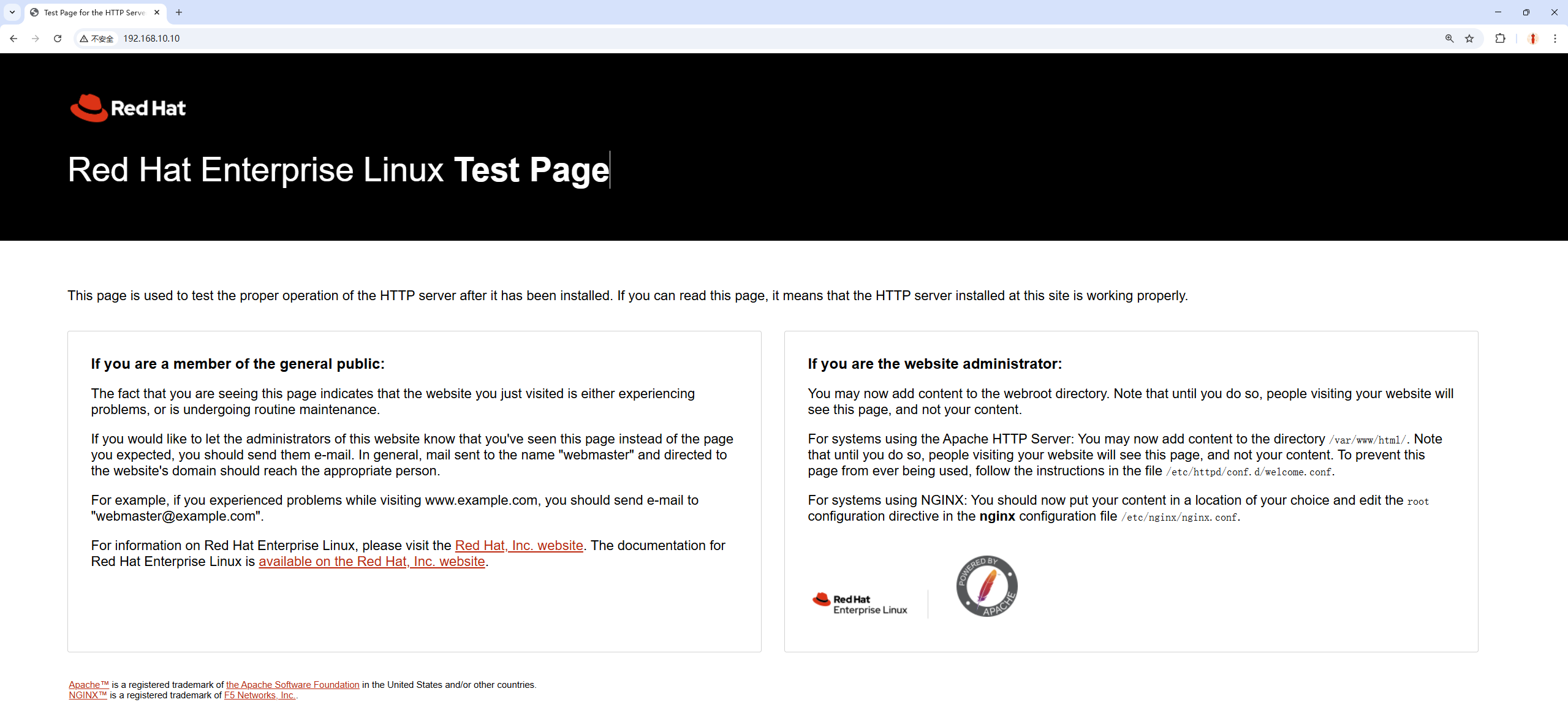

From the host machine’s browser (e.g., Google Chrome), visit http://192.168.10.10 and you’ll see Apache’s default page (Figure 10‑3).

If it fails, check that the VM’s IP is 192.168.10.10, its adapter is in host‑only mode, and your host’s VMnet1 is in the same subnet (e.g., 192.168.10.1/255.255.255.0). If you’ve forgotten how, review Figures 8‑16 and 8‑17.

Figure 10-3 Default httpd welcome page

Or, from the terminal, launch Firefox directly:

root@linuxprobe:~# firefox

10.2 Configuring service files and parameters

Installing and starting httpd is only the beginning. On Linux, configuring a service means editing its configuration files. Know where they are and what they do. Table 10‑1 lists the most important ones.

Table 10‑1 Main httpd files and their roles

| File/Path | Role |

|---|---|

| /etc/httpd | Service directory |

| /etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf | Main configuration |

| /var/www/html | Document root |

| /var/log/httpd/access_log | Access log |

| /var/log/httpd/error_log | Error log |

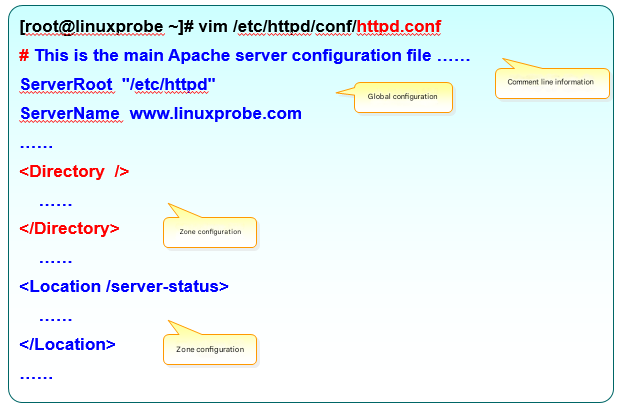

The main config can be long (358 lines in my lab), but don’t panic—lines starting with # are comments meant to explain behavior or options.

Inside the file you’ll find three kinds of content (Figure 10‑4): comments, global directives, and per‑site directives. Global directives apply to all virtual hosts and prevent duplication. Per‑site directives configure each individual sub‑site—like a cafeteria giving everyone a standard bowl of rice (global), then adding each student’s custom dishes (per‑site). Table 10‑2 shows the most common directives.

Figure 10-4 Structure of the main Apache config

Table 10‑2 Common httpd directives

| Directive | Purpose |

|---|---|

| ServerRoot | Service directory |

| ServerAdmin | Admin email |

| User | User the service runs as |

| Group | Group the service runs as |

| ServerName | Server’s hostname |

| DocumentRoot | Document root |

| Listen | IP/port to listen on |

| DirectoryIndex | Default index page |

| ErrorLog | Error log |

| CustomLog | Access log |

| Timeout | Request timeout (default 300s) |

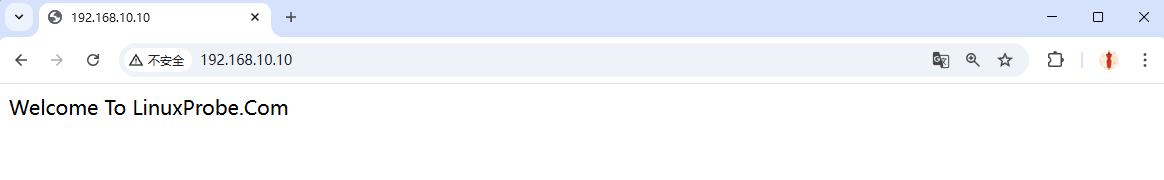

By default, DocumentRoot is /var/www/html, and most sites use index.html as the home page. Replace the default page like this:

root@linuxprobe:~# echo "Welcome To LinuxProbe.Com" > /var/www/html/index.html

Refresh the browser to see the change (Figure 10‑5).

Figure 10-5 The home page has been replaced

If you want to change the document root to /home/wwwroot, follow these steps.

Step 1: Create the directory and an index page.

root@linuxprobe:~# mkdir /home/wwwroot

root@linuxprobe:~# echo "The New Web Directory" > /home/wwwroot/index.html

Step 2: Edit the main config—set DocumentRoot and both <Directory> blocks to /home/wwwroot. Save and exit.

root@linuxprobe:~# vim /etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf

119 #

120 # DocumentRoot: The directory out of which you will serve your

121 # documents. By default, all requests are taken from this directory, but

122 # symbolic links and aliases may be used to point to other locations.

123 #

124 DocumentRoot "/home/wwwroot"

125

126 #

127 # Relax access to content within /var/www.

128 #

129 <Directory "/home/wwwroot">

130 AllowOverride None

131 # Allow open access:

132 Require all granted

133 </Directory>

134

135 # Further relax access to the default document root:

136 <Directory "/home/wwwroot">

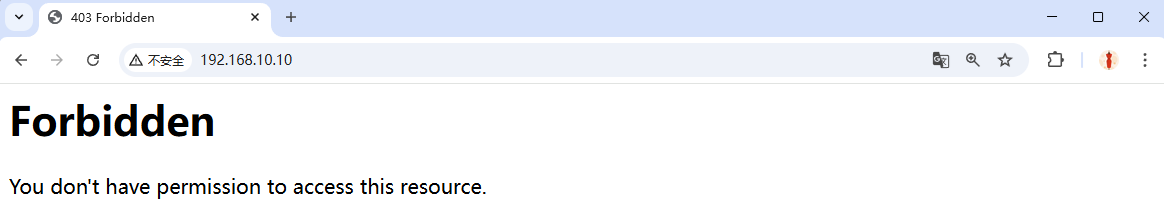

Step 3: Restart httpd and refresh the page. You’ll see “permission denied” (Figure 10‑6).

root@linuxprobe:~# systemctl restart httpd

Figure 10-6 Permission denied

10.3 The SELinux security subsystem

Figure 10-7 SELinux logo

Imagine you download a photo app and, while you’re beautifying pictures, it silently listens for passwords you type into your browser. That’s out of bounds. SELinux prevents this class of behavior: domain restrictions keep services from doing things they shouldn’t; file security contexts restrict which files a service can access.

Tips:

If UNIX permissions and the firewall are “doors and windows,” SELinux is the protective fence outside—an extra layer of safety.

I often describe SELinux domains plus file contexts as a “double lock.” Services can only access what they’re supposed to, so even if an attacker gains a foothold they can’t easily abuse a service to overreach. Sadly, SELinux is seen as complex and is often disabled. That’s not wise.

SELinux has three modes:

enforcing: apply the policy and block disallowed actions.

permissive: warn on violations, but don’t block.

disabled: no policy loaded; no checks performed.

All labs in this book use enforcing mode. Check your default in the main config; if it’s permissive or disabled, switch to enforcing:

root@linuxprobe:~# cat /etc/selinux/config

# This file controls the state of SELinux on the system.

# SELINUX= can take one of these three values:

# enforcing - SELinux security policy is enforced.

# permissive - SELinux prints warnings instead of enforcing.

# disabled - No SELinux policy is loaded.

# See also:

SELINUX=enforcing

# SELINUXTYPE= can take one of these three values:

# targeted - Targeted processes are protected,

# minimum - Modification of targeted policy. Only selected processes are protected.

# mls - Multi Level Security protection.

SELINUXTYPE=targeted

That file sets the post‑reboot default. To see the current mode:

root@linuxprobe:~# getenforce

Enforcing

To confirm that SELinux caused the earlier “permission denied,” temporarily switch to permissive (effective immediately until reboot):

root@linuxprobe:~# setenforce 0

root@linuxprobe:~# getenforce

Permissive

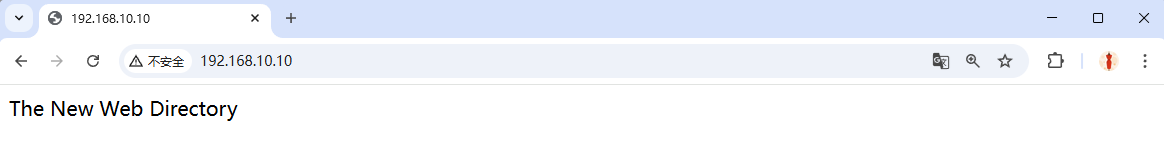

Refresh the page—you should now see the site (Figure 10‑8).

Figure 10-8 Expected content after switching to permissive

What went wrong? Apache is allowed to serve web content, but only from locations labeled for web content. We moved the document root to /home/wwwroot, and /home is for user homes. That violates policy.

Switch back to enforcing and compare labels. -Z prints SELinux contexts; -d treats the target as a directory.

root@linuxprobe:~# setenforce 1

root@linuxprobe:~# ls -Zd /var/www/html

system_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0 /var/www/html

root@linuxprobe:~# ls -Zd /home/wwwroot

unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_dir_t:s0 /home/wwwroot

An SELinux context contains user, role, type, and level. Here the type is key: httpd_sys_content_t marks web content; user_home_dir_t marks home directories.

Use semanage to set appropriate file contexts, then apply with restorecon:

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/*

root@linuxprobe:~# restorecon -Rv /home/wwwroot/

Relabeled /home/wwwroot from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_dir_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/index.html from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

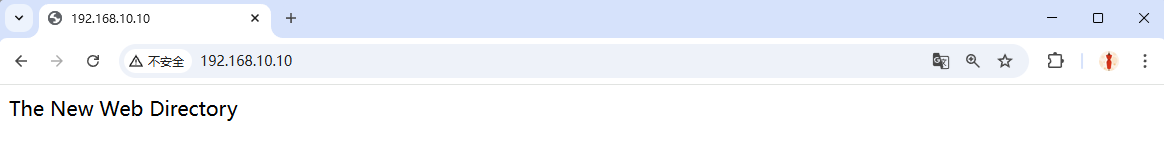

Refresh: the page renders normally again (Figure 10‑9).

Figure 10-9 Normal content after fixing labels

Tips:

RHCSA/RHCE/RHCA exams usually require a reboot before grading. Make a habit of enabling services at boot—for example,systemctl enable httpdhere.

10.4 User home pages

If you need a separate site for every user, building lots of vhosts is tedious and permission‑heavy to manage. Apache’s UserDir feature lets each user manage a personal site under their home directory.

Step 1: By default, UserDir is disabled. Edit the following file: comment out UserDir disabled, and uncomment UserDir public_html. Save the file.

root@linuxprobe:~# vim /etc/httpd/conf.d/userdir.conf

1 #

2 # UserDir: The name of the directory that is appended onto a user's home

3 # directory if a ~user request is received.

4 #

5 # The path to the end user account 'public_html' directory must be

6 # accessible to the webserver userid. This usually means that ~userid

7 # must have permissions of 711, ~userid/public_html must have permissions

8 # of 755, and documents contained therein must be world-readable.

9 # Otherwise, the client will only receive a "403 Forbidden" message.

10 #

11 <IfModule mod_userdir.c>

12 #

13 # UserDir is disabled by default since it can confirm the presence

14 # of a username on the system (depending on home directory

15 # permissions).

16 #

17 # UserDir disabled

18

19 #

20 # To enable requests to /~user/ to serve the user's public_html

21 # directory, remove the "UserDir disabled" line above, and uncomment

22 # the following line instead:

23 #

24 UserDir public_html

25 </IfModule>

26

27 #

28 # Control access to UserDir directories. The following is an example

29 # for a site where these directories are restricted to read-only.

30 #

31 <Directory "/home/*/public_html">

32 AllowOverride FileInfo AuthConfig Limit Indexes

33 Options MultiViews Indexes SymLinksIfOwnerMatch IncludesNoExec

34 Require method GET POST OPTIONS

35 </Directory>

Step 2: Create the directory and an index page in the user’s home, and make it world‑readable:

root@linuxprobe:~# su - linuxprobe

linuxprobe@linuxprobe:~$ mkdir public_html

linuxprobe@linuxprobe:~$ echo "This is linuxprobe's website" > public_html/index.html

linuxprobe@linuxprobe:~$ chmod -R 755 /home/linuxprobe

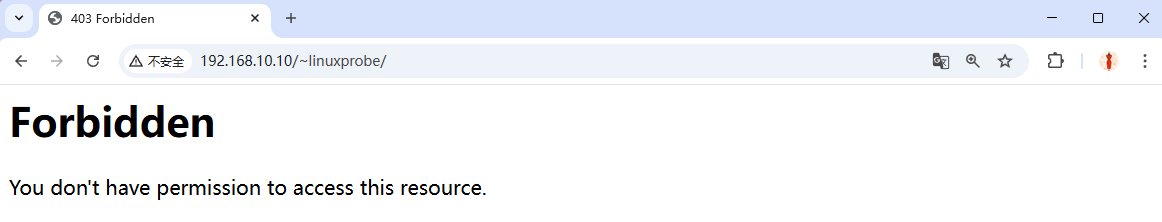

Step 3: Restart httpd and browse to /~username. You’ll see a denied page (Figure 10‑10)—that’s SELinux again.

linuxprobe@linuxprobe:~$ exit

logout

root@linuxprobe:~# systemctl restart httpd

Figure 10-10 Access to the user site is forbidden

Check relevant SELinux booleans; off means disabled, on means enabled. Enable httpd_enable_homedirs and make it persistent:

root@linuxprobe:~# getsebool -a | grep http

httpd_anon_write --> off

httpd_builtin_scripting --> on

httpd_can_check_spam --> off

httpd_can_connect_ftp --> off

httpd_can_connect_ldap --> off

httpd_can_connect_mythtv --> off

httpd_can_connect_zabbix --> off

httpd_can_manage_courier_spool --> off

httpd_can_network_connect --> off

httpd_can_network_connect_cobbler --> off

httpd_can_network_connect_db --> off

httpd_can_network_memcache --> off

httpd_can_network_redis --> off

httpd_can_network_relay --> off

httpd_can_sendmail --> off

httpd_dbus_avahi --> off

httpd_dbus_sssd --> off

httpd_dontaudit_search_dirs --> off

httpd_enable_cgi --> on

httpd_enable_ftp_server --> off

httpd_enable_homedirs --> off

root@linuxprobe:~# setsebool -P httpd_enable_homedirs=on

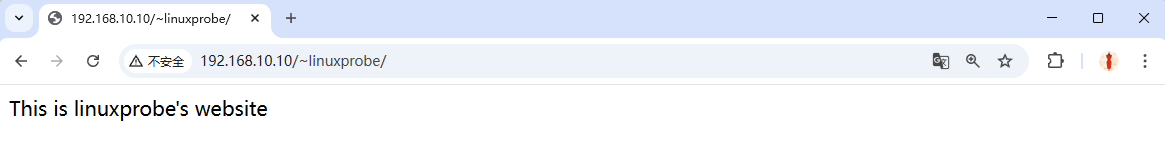

Now the user site loads (Figure 10‑11).

Figure 10-11 UserDir content loads after enabling the SELinux boolean

To restrict access to authenticated visitors, add basic authentication.

Step 1: Create the password database with htpasswd. -c creates the file the first time; the username is for web login only (it need not be a system user).

root@linuxprobe:~# htpasswd -c /etc/httpd/passwd linuxprobe

New password: Enter the password for web authentication here.

Re-type new password: Enter it again for confirmation.

Adding password for user linuxprobe

Step 2: Protect the UserDir directory and restart httpd:

root@linuxprobe:~# vim /etc/httpd/conf.d/userdir.conf

31 <Directory "/home/*/public_html">

32 AllowOverride all

#Path to save the newly generated password verification file

33 authuserfile "/etc/httpd/passwd"

#Prompt message when the user accesses the website

34 authname "My private website"

#Authentication method is password mode

35 authtype basic

#User name required for verification when accessing the website

36 require user linuxprobe

37 </Directory>

root@linuxprobe:~# systemctl restart httpd

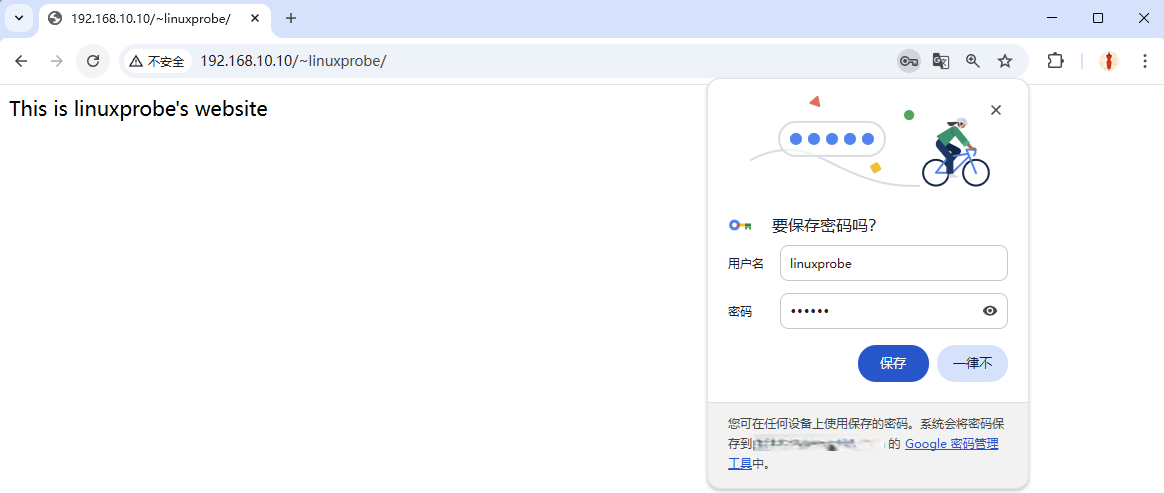

Now, visitors must enter the username and password to access a user’s site (Figures 10‑12 and 10‑13).

Figure 10-12 Authentication required

Figure 10-13 Authentication succeeds

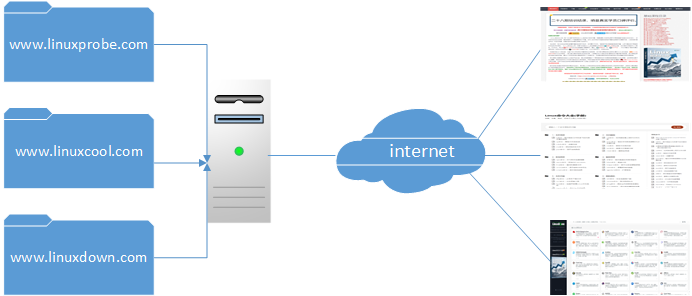

10.5 Virtual hosts

If each server could run only one website, small sites would be forced to pay for dedicated servers—wasteful and expensive. Before VPS and cloud computing, hosting providers introduced “virtual hosts” to improve utilization and lower costs.

With Apache’s virtual hosts, one server can serve multiple sites based on the requested IP, hostname, or port (Figure 10‑14).

Figure 10-14 Routing requests to different sites

Before each lab, revert the VM to a clean baseline so experiments don’t conflict.

10.5.1 By IP address

If your server has multiple IP addresses—one per site—then visiting different IPs returns different sites. Dedicated IPs can also help SEO, so this method is common and popular among site owners.

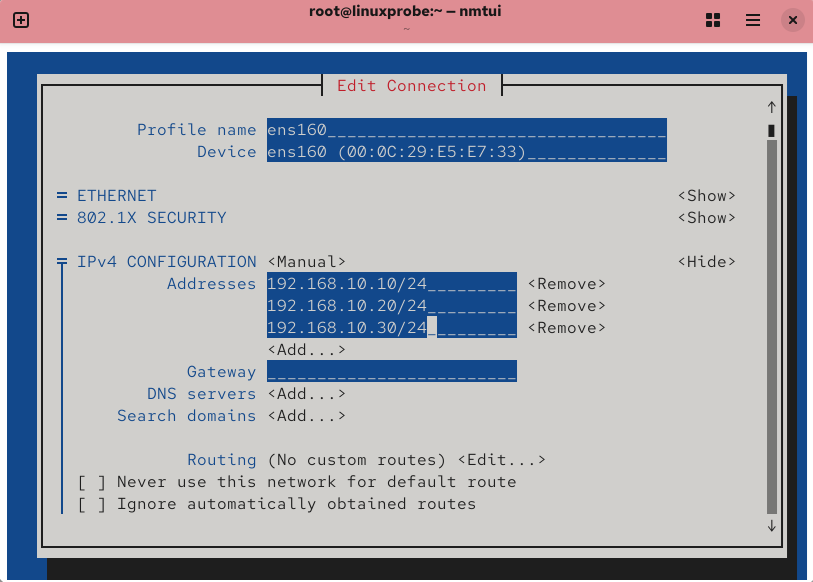

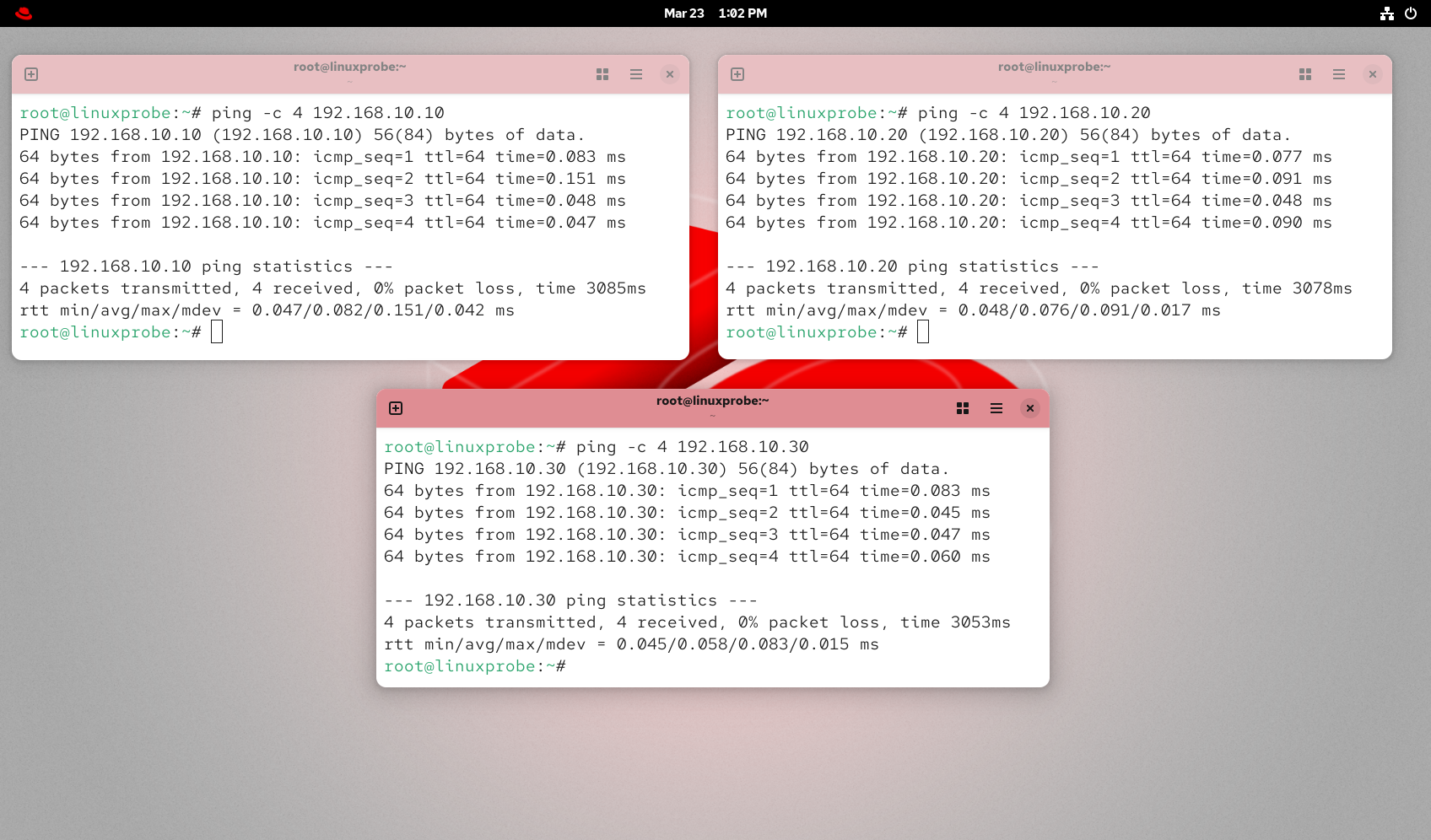

Configure the IPs (see Chapters 4 and 9), restart networking, and verify all three are reachable (Figures 10‑15 and 10‑16).

Figure 10-15 Configure IPs with nmtui

root@linuxprobe:~# nmcli connection up ens160

Connection successfully activated (D-Bus active path: /org/freedesktop/NetworkManager/ActiveConnection/3)

Figure 10-16 Test connectivity for all three IPs

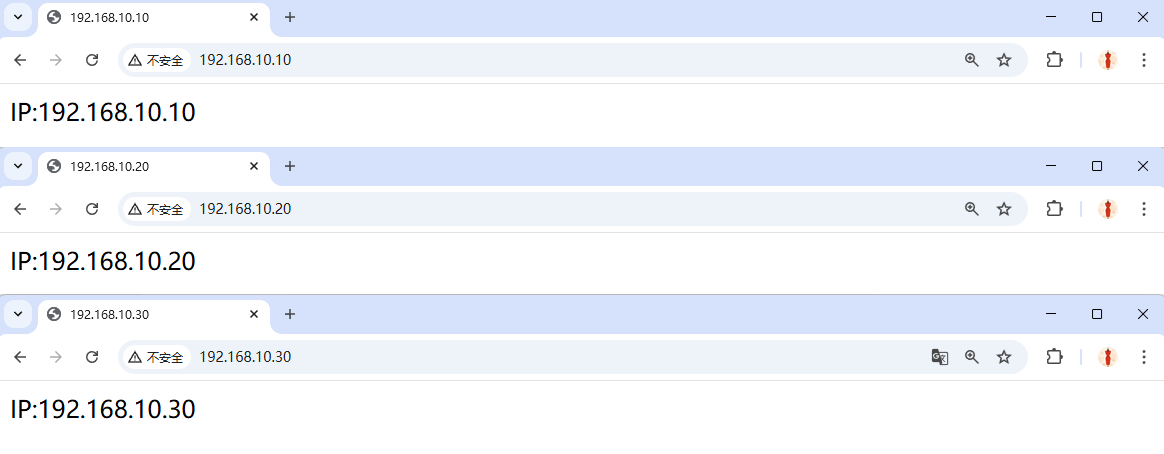

Step 1: Create three document roots and distinct index pages:

root@linuxprobe:~# mkdir -p /home/wwwroot/10

root@linuxprobe:~# mkdir -p /home/wwwroot/20

root@linuxprobe:~# mkdir -p /home/wwwroot/30

root@linuxprobe:~# echo "IP:192.168.10.10" > /home/wwwroot/10/index.html

root@linuxprobe:~# echo "IP:192.168.10.20" > /home/wwwroot/20/index.html

root@linuxprobe:~# echo "IP:192.168.10.30" > /home/wwwroot/30/index.html

Step 2: Append three IP‑based vhosts and restart httpd:

root@linuxprobe:~# vim /etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf

125 <VirtualHost 192.168.10.10>

126 DocumentRoot /home/wwwroot/10

127 ServerName www.linuxprobe.com

128 <Directory /home/wwwroot/10>

129 AllowOverride None

130 Require all granted

131 </Directory>

132 </VirtualHost>

133 <VirtualHost 192.168.10.20>

134 DocumentRoot /home/wwwroot/20

135 ServerName www.linuxprobe.com

136 <Directory /home/wwwroot/20>

137 AllowOverride None

138 Require all granted

139 </Directory>

140 </VirtualHost>

141 <VirtualHost 192.168.10.30>

142 DocumentRoot /home/wwwroot/30

143 ServerName www.linuxprobe.com

144 <Directory /home/wwwroot/30>

145 AllowOverride None

146 Require all granted

147 </Directory>

148 </VirtualHost>

root@linuxprobe:~# systemctl restart httpd

Step 3: If you see “permission denied,” fix SELinux labels on the new directories and apply them:

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/10

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/10/*

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/20

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/20/*

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/30

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/30/*

root@linuxprobe:~# restorecon -Rv /home/wwwroot

Relabeled /home/wwwroot from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_dir_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/10 from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/10/index.html from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/20 from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/20/index.html from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/30 from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/30/index.html from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Each IP now serves its own content (Figure 10‑17).

Figure 10-17 IP‑based virtual hosts

10.5.2 By hostname

When you can’t give each site its own IP, name‑based vhosts are simpler. The server needs only one IP (192.168.10.10). Because we don’t have DNS here, use /etc/hosts for testing.

Step 1: Add hostnames and verify resolution with ping:

root@linuxprobe:~# vim /etc/hosts

# Loopback entries; do not change.

# For historical reasons, localhost precedes localhost.localdomain:

127.0.0.1 localhost localhost.localdomain localhost4 localhost4.localdomain4

::1 localhost localhost.localdomain localhost6 localhost6.localdomain6

192.168.10.10 www.linuxprobe.com www.linuxcool.com www.linuxdown.com

root@linuxprobe:~# ping -c 4 www.linuxprobe.com

PING www.linuxprobe.com (192.168.10.10) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from www.linuxprobe.com (192.168.10.10): icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=0.869 ms

64 bytes from www.linuxprobe.com (192.168.10.10): icmp_seq=2 ttl=64 time=0.141 ms

64 bytes from www.linuxprobe.com (192.168.10.10): icmp_seq=3 ttl=64 time=0.099 ms

64 bytes from www.linuxprobe.com (192.168.10.10): icmp_seq=4 ttl=64 time=0.048 ms

--- www.linuxprobe.com ping statistics ---

4 packets transmitted, 4 received, 0% packet loss, time 3043ms

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 0.048/0.289/0.869/0.336 ms

root@linuxprobe:~#

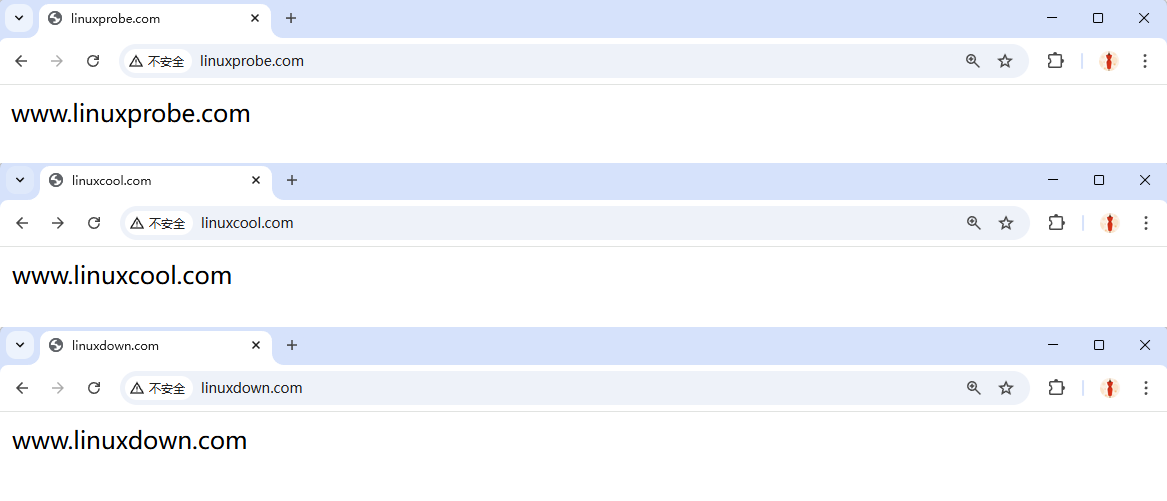

Step 2: Create three document roots and index pages:

root@linuxprobe:~# mkdir -p /home/wwwroot/linuxprobe

root@linuxprobe:~# mkdir -p /home/wwwroot/linuxcool

root@linuxprobe:~# mkdir -p /home/wwwroot/linuxdown

root@linuxprobe:~# echo "www.linuxprobe.com" > /home/wwwroot/linuxprobe/index.html

root@linuxprobe:~# echo "www.linuxcool.com" > /home/wwwroot/linuxcool/index.html

root@linuxprobe:~# echo "www.linuxdown.com" > /home/wwwroot/linuxdown/index.html

Step 3: Append the hostname‑based vhosts and restart httpd:

root@linuxprobe:~# vim /etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf

151 <VirtualHost *:80>

152 ServerName www.linuxprobe.com

153 DocumentRoot /home/wwwroot/linuxprobe

154 <Directory /home/wwwroot/linuxprobe>

155 AllowOverride None

156 Require all granted

157 </Directory>

158 </VirtualHost>

159 <VirtualHost *:80>

160 ServerName www.linuxcool.com

161 DocumentRoot /home/wwwroot/linuxcool

162 <Directory /home/wwwroot/linuxcool>

163 AllowOverride None

164 Require all granted

165 </Directory>

166 </VirtualHost>

167 <VirtualHost *:80>

168 ServerName www.linuxdown.com

169 DocumentRoot /home/wwwroot/linuxdown

170 <Directory /home/wwwroot/linuxdown>

171 AllowOverride None

172 Require all granted

173 </Directory>

174 </VirtualHost>

root@linuxprobe:~# systemctl restart httpd

Step 4: Fix SELinux labels for the new directories, then apply them:

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/linuxprobe

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/linuxprobe/*

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/linuxcool

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/linuxcool/*

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/linuxdown

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/linuxdown/*

root@linuxprobe:~# restorecon -Rv /home/wwwroot/

Relabeled /home/wwwroot from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_dir_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/linuxprobe from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/linuxprobe/index.html from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/linuxcool from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/linuxcool/index.html from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/linuxdown from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/linuxdown/index.html from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Now each hostname serves its own content (Figure 10‑18).

Figure 10-18 Name‑based virtual hosts

10.5.3 By port

Port‑based vhosts route requests to different sites based on the TCP port. This is the trickiest form, because you must consider Apache’s configuration, SELinux’s port policy, and the firewall. Ports such as 80/443/8080 are permitted by policy; other ports are blocked unless you extend it.

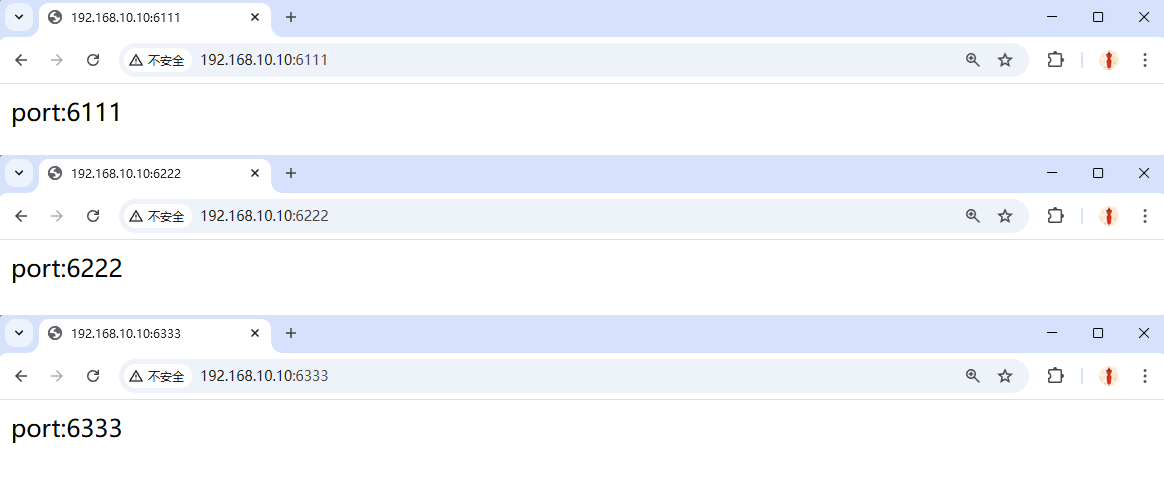

Step 1: Create three document roots and index pages that identify each port:

root@linuxprobe:~# mkdir -p /home/wwwroot/6111

root@linuxprobe:~# mkdir -p /home/wwwroot/6222

root@linuxprobe:~# mkdir -p /home/wwwroot/6333

root@linuxprobe:~# echo "port:6111" > /home/wwwroot/6111/index.html

root@linuxprobe:~# echo "port:6222" > /home/wwwroot/6222/index.html

root@linuxprobe:~# echo "port:6333" > /home/wwwroot/6333/index.html

Step 2: Add Listen directives for the three ports:

root@linuxprobe:~# vim /etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf

46 #Listen 12.34.56.78:80

47 Listen 80

48 Listen 6111

49 Listen 6222

50 Listen 6333

Step 3: Append the port‑based vhost sections and restart httpd:

root@linuxprobe:~# vim /etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf

127 <VirtualHost 192.168.10.10:6111>

128 DocumentRoot /home/wwwroot/6111

129 ServerName www.linuxprobe.com

130 <Directory /home/wwwroot/6111>

131 AllowOverride None

132 Require all granted

133 </Directory>

134 </VirtualHost>

135 <VirtualHost 192.168.10.10:6222>

136 DocumentRoot /home/wwwroot/6222

137 ServerName www.linuxprobe.com

138 <Directory /home/wwwroot/6222>

139 AllowOverride None

140 Require all granted

141 </Directory>

142 </VirtualHost>

143 <VirtualHost 192.168.10.10:6333>

144 DocumentRoot /home/wwwroot/6333

145 ServerName www.linuxprobe.com

146 <Directory /home/wwwroot/6333>

147 AllowOverride None

148 Require all granted

149 </Directory>

150 </VirtualHost>

Step 4: Because we’re serving content from /home/wwwroot, set the SELinux labels appropriately and apply them:

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/6111

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/6111/*

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/6222

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/6222/*

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/6333

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t /home/wwwroot/6333/*

root@linuxprobe:~# restorecon -Rv /home/wwwroot/

Relabeled /home/wwwroot from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_dir_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/6111 from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/6111/index.html from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/6222 from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/6222/index.html from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/6333 from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

Relabeled /home/wwwroot/6333/index.html from unconfined_u:object_r:user_home_t:s0 to unconfined_u:object_r:httpd_sys_content_t:s0

root@linuxprobe:~# systemctl restart httpd

Job for httpd.service failed because the control process exited with error code.

See "systemctl status httpd.service" and "journalctl -xeu httpd.service" for details.

Why the failure? SELinux permits only certain HTTP ports by default. List the allowed ones:

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage port -l | grep http

http_cache_port_t tcp 8080, 8118, 8123, 10001-10010

http_cache_port_t udp 3130

http_port_t tcp 80, 81, 443, 488, 8008, 8009, 8443, 9000

pegasus_http_port_t tcp 5988

pegasus_https_port_t tcp 5989

Step 5: Add our three ports to http_port_t so Apache is allowed to listen on them (this persists across reboots):

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage port -a -t http_port_t -p tcp 6111

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage port -a -t http_port_t -p tcp 6222

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage port -a -t http_port_t -p tcp 6333

root@linuxprobe:~# semanage port -l | grep http

http_cache_port_t tcp 8080, 8118, 8123, 10001-10010

http_cache_port_t udp 3130

http_port_t tcp 6333, 6222, 6111, 80, 81, 443, 488, 8008, 8009, 8443, 9000

pegasus_http_port_t tcp 5988

pegasus_https_port_t tcp 5989

Step 6: Open the ports in the firewall, reload, and restart httpd:

root@linuxprobe:~# firewall-cmd --permanent --add-port=6111/tcp

success

root@linuxprobe:~# firewall-cmd --permanent --add-port=6222/tcp

success

root@linuxprobe:~# firewall-cmd --permanent --add-port=6333/tcp

success

root@linuxprobe:~# firewall-cmd --reload

success

root@linuxprobe:~# systemctl restart httpd

Now each port serves its own site (Figure 10‑19).

Figure 10-19 Port‑based virtual hosts

10.6 Access control in Apache

Apache can restrict access based on source hostname or IP, or even on the browser’s User‑Agent. Use Allow to permit, Deny to block, and Order to define the evaluation order. With Order allow,deny, Apache first checks the allow rules; if they match, the request is allowed, otherwise it’s denied by default.

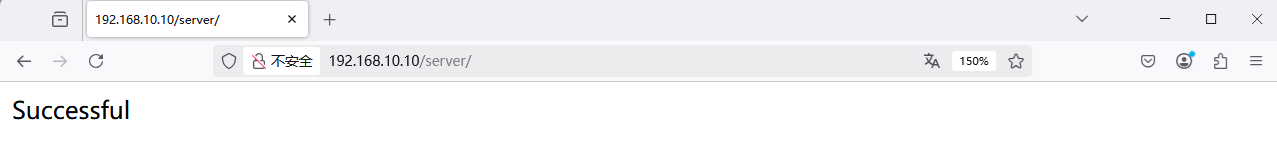

Step 1: Create a subdirectory and an index page that contains the word Successful:

root@linuxprobe:~# mkdir /var/www/html/server

root@linuxprobe:~# echo "Successful" > /var/www/html/server/index.html

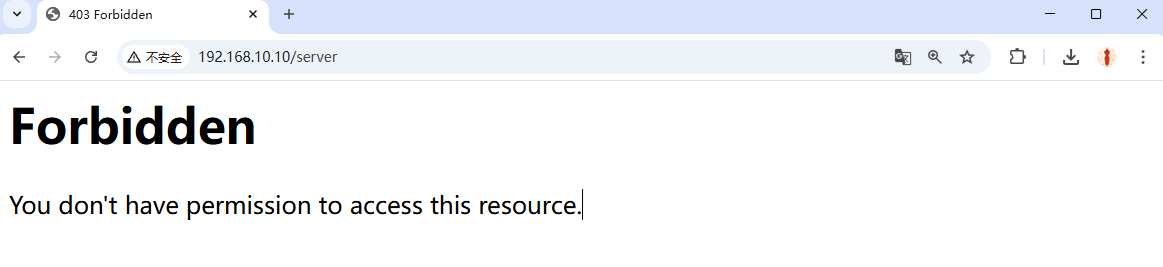

Step 2: Restrict by browser. The rules below allow only Firefox to load the page; all other requests are denied. Restart httpd and test—Firefox succeeds (Figure 10‑20); other browsers are rejected (Figure 10‑21).

root@linuxprobe:~# vim /etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf

163 <Directory "/var/www/html/server">

164 SetEnvIf User-Agent "Firefox" ff=1

165 Order allow,deny

166 Allow from env=ff

167 </Directory>

root@linuxprobe:~# systemctl restart httpd

root@linuxprobe:~# systemctl enable httpd

Created symlink '/etc/systemd/system/multi-user.target.wants/httpd.service' → '/usr/lib/systemd/system/httpd.service'.

Figure 10-20 Firefox is allowed

Figure 10-21 Other browsers are denied

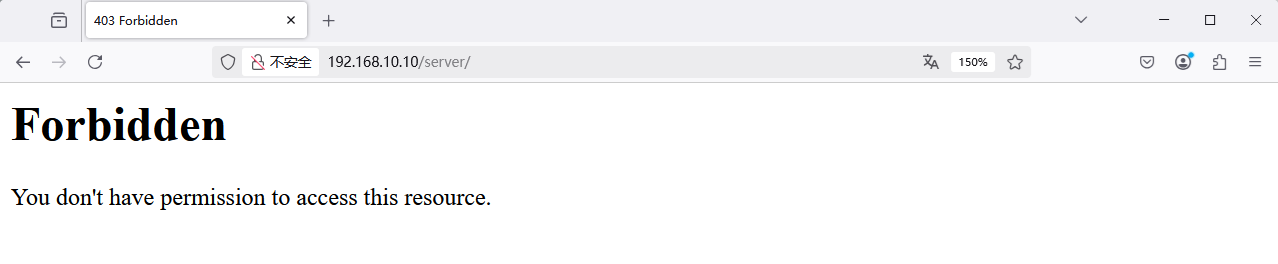

You can also control access by source IP. The rules below allow only 192.168.10.20. After restarting httpd, requests from the server itself (192.168.10.10) are denied (Figure 10‑22).

root@linuxprobe:~# vim /etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf

161 <Directory "/var/www/html/server">

162 Order allow,deny

163 Allow from 192.168.10.20

164 </Directory>

root@linuxprobe:~# systemctl restart httpd

Figure 10-22 Access denied by IP

Review Questions

-

What is a web service?

Answer: A service that lets users access internet resources via a browser. -

Compared to Nginx, what’s Apache’s biggest advantage?

Answer: Cross‑platform support, strong security model, and a fast, reliable, simple extension API. -

If no custom index page exists, what will Apache show?

Answer: A default welcome page. -

Summarize the roles of global directives, per‑site directives, and comments in

httpd.conf.

Answer: Global directives apply to all virtual hosts; per‑site directives configure each site; comments explain options and features. -

What does SELinux do?

Answer: It confines services to the resources and actions appropriate to their roles. -

You run

getenforceand seePermissive. Is that enforcing mode?

Answer: No. Enforcing isEnforcing;Permissiveonly warns about violations. -

After setting file contexts with

semanage fcontext, what command applies them immediately?

Answer:restorecon(often with-Rv). -

How do you list HTTP‑related SELinux booleans?

Answer:getsebool -a | grep http. -

On what bases can Apache build virtual hosts?

Answer: IP address, hostname (domain), or port number. -

Compared with IP‑ or name‑based vhosts, what’s special about port‑based vhosts?

Answer: You must ensure Apache listens on the ports, allow them in SELinux policy (semanage port), and open them in the firewall.